It all started innocently enough – a casual observation over lunch with Mei in the university cafeteria. “Have you ever noticed,” I said, gesturing wildly with a fork full of questionable pasta, “that Derek from Accounting does the exact same sequence of movements every time he approaches Jessica at reception? It’s like watching a bizarre courtship ritual.”

Mei glanced up from her molecular modeling papers. “You mean like those birds you were obsessed with last month?”

She was referring to my three-week deep dive into avian mating displays that had culminated in me constructing a life-sized model of a bower bird’s display arena in our living room. I’d covered the entire floor with blue objects arranged in precise patterns, convinced I could quantify the aesthetic principles that female bower birds find attractive. The experiment ended when our landlord conducted an unexpected inspection and found me squatting in the middle of a circle made from blue pens, paperclips, and several disassembled electronics.

“Exactly like that!” I exclaimed, nearly knocking over my coffee. “Look, humans are just animals with delusions of rationality. We’ve got these deeply encoded behavioral patterns that we’re not even conscious of.”

Three days and approximately forty-seven cups of coffee later, I had established a semi-permanent observation post near the office kitchen. My notebook was filled with timestamps, behavioral markers, and increasingly elaborate taxonomic categories. The security guard had already questioned me twice, but fortunately my official university ID badge and enthusiastic explanation about “behavioral ethology in workplace dynamics” was enough to convince him I belonged there.

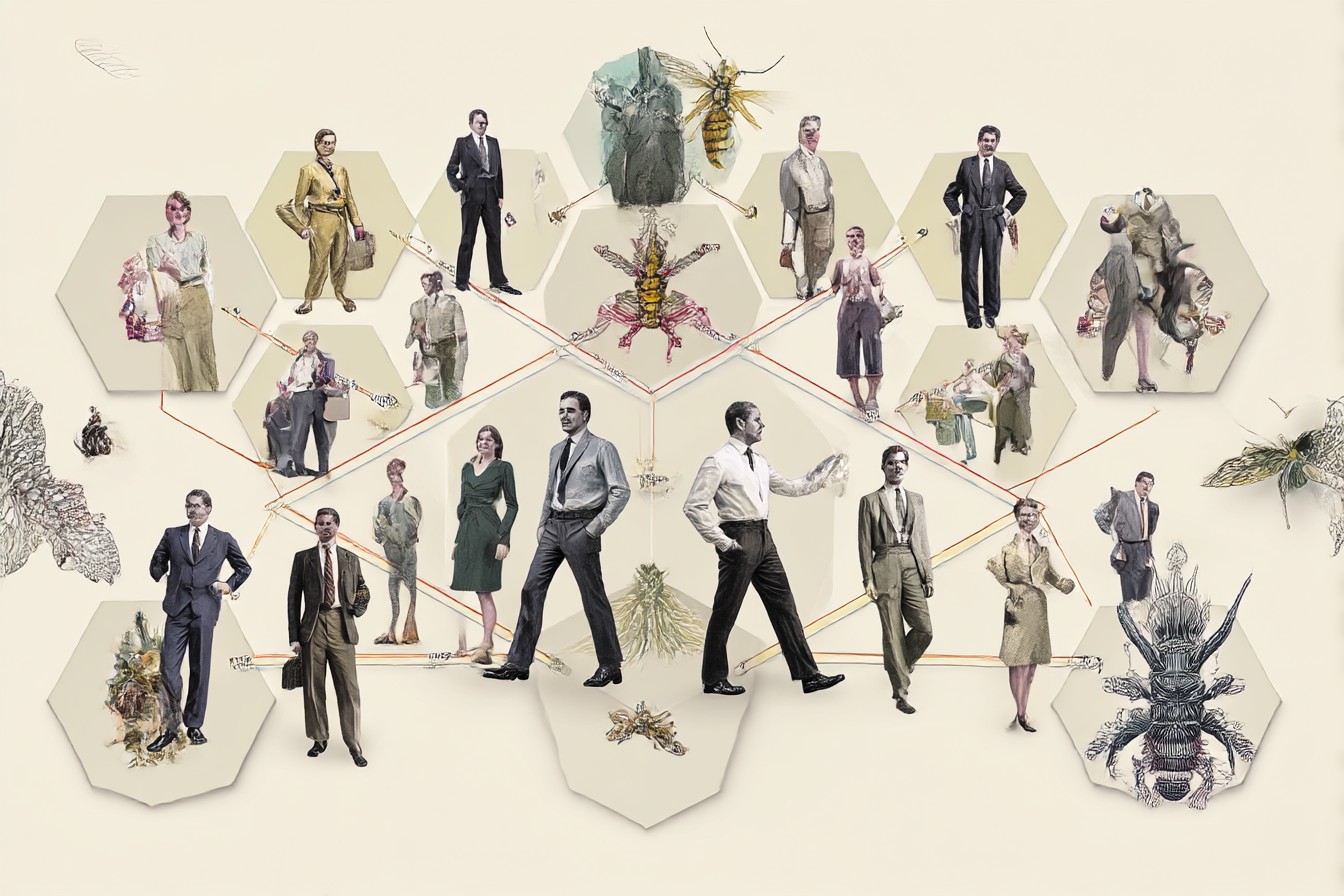

The preliminary data was fascinating. Human courtship behaviors in the office environment showed remarkable consistency across demographic categories. I’d identified seven distinct patterns of approach, three categories of preening behaviors, and what appeared to be ritualized territory marking through strategic placement of personal items in common areas.

“Jamie,” Josh sighed when I arrived at his physics department office with my preliminary findings, “this is how restraining orders happen.”

“But the data, Josh!” I spread my observation charts across his desk, knocking several important-looking papers to the floor. “Look at the consistency in these approach patterns! Subject M42 performs the exact same sequence – coffee acquisition, casual hallway crossing, document-based pretext interaction – every Tuesday and Thursday at approximately 10:15 AM when attempting to interact with Subject F19!”

Josh pinched the bridge of his nose – a gesture I’ve documented extensively as “exasperation display behavior #4” among my friends. “Have you considered that normal people just call this ‘having a crush’?”

“Reductive terminology!” I waved dismissively. “I’m developing a comprehensive taxonomic system based on observable behavioral markers. I’ve already identified six distinct mating strategy archetypes.”

The taxonomic system evolved rapidly over the next two weeks. I expanded my observation territory to include three additional departments and the campus coffee shop. My methodology improved with the addition of timed behavioral sampling and frequency counts of specific interaction types. I’d never been so scientifically invigorated since the time I attempted to measure the emotional response patterns of houseplants exposed to different genres of music. (The results were inconclusive, though the snake plant definitely seemed to enjoy jazz fusion more than expected.)

The first archetype I identified was what I termed “The Territorial Display Specialist” – typically male, characterized by loud vocalization in group settings, strategic positioning in meeting rooms to maximize visibility, and frequent reference to accomplishments using precise numerical values. Their approach pattern typically involved creating situations requiring their expertise, then performing exaggerated helpful behaviors while maintaining maximum physical proximity to their target.

“Ah yes,” said Dr. Khatri when I excitedly shared this category with her during our weekly advisory meeting. “You’ve scientifically rediscovered the office braggart. Groundbreaking.”

Her sarcasm didn’t deter me. By week three, I had expanded my taxonomy to include:

The Selective Resource Provider – These individuals used strategic gift-giving and favor-doing as their primary mating strategy. The pattern was remarkably consistent: begin with minor offerings (coffee, snacks), escalate to work-related assistance, then transition to personalized items demonstrating attention to the target’s preferences. The frequency distribution of these behaviors formed a perfect sigmoid curve when plotted against perceived reciprocal interest.

The Proximity Maintainer – Perhaps the most risk-averse strategy, characterized by gradually decreasing the average distance between workspaces through a series of seemingly coincidental location changes. One subject managed to relocate their entire workstation over a period of six weeks, moving approximately 1.2 meters per week until achieving a final position with direct line of sight to their courtship target.

The Plumage Displayer – These individuals demonstrated cyclical variation in attire, grooming, and accessory selection correlated with anticipated interaction probability. Fascinating quantitative indicators included 37% increase in cologne/perfume application, 22% increase in time spent on hair preparation, and selective deployment of conversation-initiating items (unique jewelry, graphic t-shirts with obscure references, etc.).

The Alliance Builder – This sophisticated strategy involved creating social pathways to targets through mutual connections. The pattern typically followed a hub-and-spoke model of relationship development, with careful cultivation of friendships with the target’s existing social group. The most advanced practitioners demonstrated remarkable patience, sometimes spending months establishing these allied relationships before attempting direct courtship behaviors.

The Vulnerability Performer – Characterized by strategic self-disclosure calibrated to elicit nurturing responses. These individuals demonstrated remarkable sensitivity to feedback cues, adjusting the intensity and nature of disclosed vulnerabilities based on target reactions. The most successful maintained a carefully optimized ratio of strength demonstrations to vulnerability displays (approximately 3:1 in most effective cases).

My experiment took an unexpected turn when Derek from Accounting – one of my primary subjects and a textbook Territorial Display Specialist – cornered me by the printer.

“I know what you’re doing,” he said, lowering his voice conspiratorially.

My heart rate increased by approximately 24 beats per minute. Had my research methodology been compromised? I clutched my notebook protectively against my chest.

“You’re studying us,” he continued, glancing around to ensure we weren’t overheard. “I’ve seen you watching and taking notes. You’re trying to figure out who’s interested in whom.”

“I’m conducting behavioral research on intraoffice social dynamics with emphasis on potential mating strategy variants,” I corrected, then immediately regretted the precision of my explanation.

Derek’s expression shifted to what my coding system identified as “conspiratorial engagement pattern.” “So you know who likes who around here. I need intelligence on Jessica from reception. What have you observed about her response patterns to my conversation initiations?”

And thus began the unexpected commercialization phase of my research. Within three days, I had been approached by seven different employees seeking insights on their courtship effectiveness. By the end of the week, I was holding clandestine consultation sessions in the third-floor supply closet, reviewing my observational data with lovesick accountants, IT specialists, and one particularly anxious department head.

“Your approach sequence demonstrates classic Territorial Display characteristics,” I explained to Marcus from Marketing, reviewing his behavioral charts. “However, your target appears more responsive to Vulnerability Performer strategies based on her interaction history. I recommend recalibrating your approach to include more selective self-disclosure events and fewer accomplishment references.”

Two successful date initiations later, word of my “services” had spread beyond the building. I began receiving emails from employees I’d never met, requesting consultations and strategy recommendations. One particularly grateful client brought me homemade cookies after successfully implementing my suggested transition from Proximity Maintainer to Selective Resource Provider strategy.

The ethical implications of my work became increasingly complicated. Was I manipulating social dynamics by providing this information? Was I responsible for the outcomes of my recommendations? These questions consumed my evening discussions with Mei, who alternated between amusement and concern at what she called my “accidental dating consultancy.”

“The fundamental problem,” I explained while pacing our kitchen at 2 AM, “is that I’ve shifted from observer to participant in the experimental ecosystem. I’ve violated basic principles of observational research by becoming a variable in the system I’m studying!”

Mei looked up from her quantum computing simulations. “Or maybe you’ve just helped some awkward people be slightly less awkward around their crushes.”

The situation reached its climax during the department’s quarterly social event. I arrived to find almost every subject in my study implementing strategies I had recommended with varying degrees of success. The dance floor had become a fascinating living laboratory of courtship behaviors that I had directly influenced.

As I stood observing from the punch bowl, Dr. Khatri appeared beside me.

“Maxwell,” she said, surveying the social dynamics unfolding before us, “why am I hearing that you’ve become some kind of office romance consultant?”

I winced. “It’s not exactly — I mean, I was conducting legitimate behavioral research on mating strategies in confined professional environments, and then subjects became aware of the observation and requested access to my findings, and then—”

She held up her hand to stop my rambling explanation. “Your grant application said you were researching ‘interpersonal communication optimization in professional settings.'”

“Yes! Exactly!” I gestured enthusiastically at the dance floor, where Derek was demonstrating a textbook vulnerability display to a surprisingly receptive Jessica. “Empirical results suggest a 63% increase in successful interaction initiation following strategy optimization!”

Dr. Khatri sighed – the deep, weary sigh of someone who has supervised my research for three years and has developed specialized respiratory responses. “Only you would accidentally create a scientifically validated dating service while trying to study office behavior.”

She wasn’t wrong. My attempt at objective behavioral observation had transformed into an active intervention program. My taxonomy of office mating strategies had evolved from theoretical classification to practical application guide. And somewhere along the way, I’d helped forge at least four budding relationships that showed promising stability metrics.

Science is often full of unexpected outcomes. Sometimes you set out to measure one thing and end up discovering another entirely. My research had taken an unplanned direction, but the results were undeniably interesting – and oddly, more immediately useful than much of my previous work.

As I watched my research subjects navigate their courtship rituals with newly informed strategy, I couldn’t help but feel a strange sense of satisfaction. For once, my scientific obsession had resulted in people being happier rather than confused, concerned, or covered in experimental residue.

Perhaps not all scientific pursuits need to end with publishable results or theoretical breakthroughs. Sometimes they just lead to Derek from Accounting finally getting that date with Jessica from reception – and honestly, based on their behavioral compatibility metrics, I give them a solid 78% chance of relationship viability.